Lightweight 1911 Pattern Pistols

I am not going to get too bogged down in what does or does not constitute a 1911 pattern automatic in this article. For this work, it will mean a single-action semi-automatic pistol whose lineage from the full-size all steel 1911 is apparent. The lightweight can be a full 5" gun, a Commander-size, or one of the more compact versions sporting a 3 or 3 1/2" barrel.

This piece will explore why these pistols have a following, shooting observations, as well as special "problems" that may crop up with the aluminum-frame pistols. (Polymer-frame guns are not discussed.) I will also give my own subjective views on both their strong and weak points.

It is a fair statement that Mr. Browning's 1911 remains a popular gun after many handguns designed after its birthday have faded from the shooting scene. I strongly suspect that more 1911 pattern pistols are produced domestically than any other American-made handgun. This might not be true worldwide, but I'll bet a sizeable percentage of non-US handgun owners have them…or would if they could.

Not surprisingly there are several variations on the 1911 theme and lightweight versions with aluminum frames are but one.

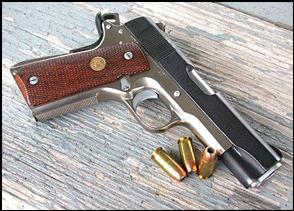

This Springfield Armory 5" Lightweight has an aluminum alloy frame. This one was fitted with a Ed Brown grip safety several years ago. Since that time dimensional changes call for a 0.220" radius rather than the 0.25" required for most. It has a Brown sear and hammer and an STI trigger. Anti-skid tape covers the front strap. Being an older version it also has the more squared off front grip strap. Of my lightweight 1911's, this one sees the most use. The 1911 pattern pistol in lightweight form can be a pretty useful item. Are they essential? Probably not, but they are nice for some purposes or circumstances.

Why a Lightweight? This is a good question and I'll give my observations and best guesses. It seems that the more popular handgun models eventually do come out in a lighter version. If a handgun is popular, it seems that many manufacturers will offer it in several variations to get as much of that market share as possible. Advertising always stresses a particular gun's strong points but never the weak. (We'll look into some of the problem areas a bit later.) Advertising can be geared to helping a potential buyer "believe" that they really do "need" this version of the gun in question. Many of the newer handgun models stress lightweight. Look at the ultra-light S&W revolvers, the scads of lightweight polymer-frame pistols, as well as the continuation of aluminum frame standards like the Colt Commander, SIG-Sauer service handguns, as well as Glocks. All of these use frame materials lighter than traditional steel.

So am I saying that gun makers are creating a false need to increase sales? Not necessarily, although the main focus of any company rests at the bottom line. They want to stay in business and need sales to do this. If essentially the same gun as an all-steel one can be made by simply substituting aluminum alloy for steel, they can offer at least one other variation on a successful theme with relatively little R&D or start up costs.

The more compact lightweights include the Colt Defender (left) and the mainstay Commander on the right. Many do not consider 1911 pattern pistols smaller than the Commander to be true 1911's and reliability issues are frequently cited. While it's no secret that I personally own no 1911 pistols smaller than the Commander, more than a few folks tote such diminutive forty-fives as the Defender. For this article the important factors concerning its special "needs" compared to all-steel guns are the same.

I will offer my opinions as a shooter and former police officer on the role of the lightweight handgun in general and the 1911 pattern pistol in particular.

We frequently hear that the only thing the lightweight 1911 does is to carry easier. While it is true that they are lighter, for myself they seem to be quicker from the holster to the first shot! It seems that they just get "on target" quicker for me…for the first shot which very well might be the most important in self-defense scenarios.

There's not much way around there being more felt recoil in a lighter pistol of the same type. (The LW 5" SA weighs about a half-pound less than its steel frame counterparts.) The interesting thing is that it makes no difference in speed if firing one shot on one target and moving to another. The gun doesn't have to be down in from recoil before moving to another target. I verified this with a timer using myself and a friend as guinea pigs. There is a slight increase in the time between individual shots on a single target. This proved true for both myself and my friend, who is extremely quick. So, if in a shoot-out situation and you engaging multiple targets, we probably won't see a difference in time between a single hit on each. If one requires a second or third shot, the split goes up (slightly) and translates to a tiny bit slower response time for secondary targets. I do not remember the exact times but it seems that there were but a few hundredths of a second difference. How much of a factor this might or might not be in real life I leave for each of us to decide based on our own experiences and perceptions.

Problems with Lightweight 1911's: The aluminum frame 1911's are nice to carry despite a bit more actual felt recoil when firing, but to have this we also inherit a few problems. Some are easily overcome and one might be impossible to totally eliminate. Let's talk about it first.

Longevity: This is usually the reason cited for not owning a LW rather than all steel 1911…and there is some truth to it. The aluminum frame guns probably do not hold up to as many rounds as the steel frame ones. The question is how many is "many"? If you shoot perhaps 100 full-power rounds per month through your LW, that would be about 1200 per year. I've heard estimates suggesting that the LW is good for 15 to twenty thousand rounds before the frame will crack. I have no idea if this is true or not, but assuming that both are "good numbers" and pick one in the middle at 17,500 rounds. Doing the math indicates that our pistol should be good to go for over 14 years at 100 full-power shots per month. This assumes that the recoil spring is changed when needed. I honestly believe that using a bit stronger recoil spring and a shock buffer can significantly extend the useful life of the LW aluminum frame. This would cushion the impact transferred from the steel slide to the aluminum frame via the flange on the recoil spring guide. The factory standard recoil spring for the full size 45-caliber 1911 is 16 pounds. I use an 18.5-lb spring with no problems and I also use a shock buff. If you are concerned with either or both causing malfunctions, why not just use them at the range and then revert to the factory standard recoil spring and no buffer when carrying for serious purposes? Mine stays set up with the slightly heavier spring as well as the buffer as this combination has caused me absolutely zero problems in my guns. The same might or might not be true in others.

I believe that using the polymer buffer along with the slightly stronger 18.5-lb recoil spring extends the life of the aluminum alloy frame. Others disagree. I suggest that if you have reliability concerns, use the slightly heavier spring…or at least the buffer for practice and remove when you clean the pistol before carrying.

I do not subscribe to the theory that the 18.5-lb spring damages the gun when it "slams" the slide forward. The 5" Delta Elite fires the 10mm and uses even heavier springs. If you do, just use the 16-lb. spring and a buffer when practicing.

The relatively few lightweight frames I've seen cracked have been on Colt Commanders and most eminate from the hole through which the slide stop passes…or are in that immediate area. Frequently drilling a small hole at the end of the crack can stop its continued growth. Of course this looks like hell.

I don't think the LW 1911 pattern pistol is best served with +P ammunition in .45 ACP. Assuming equal bullet weight, the +P round should translate into that bullet being pushed faster than the standard velocity one. That translates into the slide being driven rearward harder when the gun is fired. It also means more felt recoil. For the lightweight pistols I suggest standard velocity ammunition. If a person is bound and determined to use +P, I suggest using it only for ocassional practice (with a buffer) and then as a carry load if that is intended. My own lightweight 1911's use standard pressure ammunition for carry and the handloaded equivalents for practice.

The LW 1911 might not have the longevity of its all-steel brethren, but neither is it waiting to just crumble, either. A little prevention and common sense should allow a shooter to do quite a bit of shooting with one with no problems.

Feed Ramps: On many of the lightweight 1911 pattern pistols the feed ramp will be the traditional setup in which the frame provides the lower portion of the system. Aluminum is softer than steel. It will dent and gouge easier and is usually covered with a hard finish called anodizing. This protects the aluminum alloy and should not be removed. Bare aluminum can be damaged fairly easily if bullets with sharp edges are used and particularly so if the magazines used don't angle the bullet upward. If the cartridge "dips" or hits the ramp straight on as it is stripped from the magazine, even an anodized ramp area can eventually get pretty dinged up.

In my experience, ammunition having rounded edges around the bullet's meplat or hollow point is not harmful to the aluminum lightweight 1911 frame portion of the feed ramp. (L-R: Handloaded 200-gr. CSWC, handloaded 230-gr. FMJ FP, Winchester 230-gr. Ranger JHP, Winchester 230-gr. FMJ.)

Magazine followers can wreak havoc on an aluminum frame gun's feed system. If the follower is free to move forward past the front of the magazine tube as the last round is stripped and chambered, it can cause dings in the ramp. Fortunately these are usually below where the bullet initially contacts it but the problem can be avoided altogether. I suggest using only magazines in which the follower design does not allow it to possibly move out of the magazine body and contact the ramp. Examples would include some of the old Randall magazines as well as Wilson and Tripp magazines.

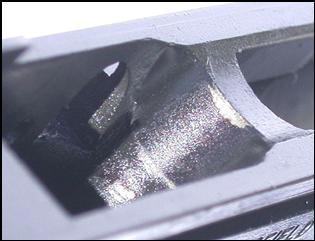

Here is the wear apparent on my moderately used SA Lightweight 5". Note the dings toward the bottom of the ramp. Traditional magazines caused these. Their followers could contact this portion of the feed ramp. The wear at the top is just from use. Using a magazine with a "captive" follower as shown by the Tripp follower in the Randall magazine at the right eliminates damage to the ramp from the follower. It should be noted that not all traditional magazines having the "non-captive" followers cause problems, but I've seen enough that I don't use them in the lightweight aluminum frame 1911's.

The magazine followers on the left and middle should work fine with the LW 1911. The one having the traditional follower (right) could damage the feed ramp. It is my understanding that current versions of the SA 5" lightweight have a one-piece steel ramp to completely eliminate potential damage.

Plunger Tube: Aluminum is simply softer than steel and a vital part of the 1911 is staked to the frame. Of course this is the plunger tube. It simply holds the spring-loaded plungers that tension both the slide stop and the thumb safety. If too much up/down pressure is applied to the plunger tube it can become loose. Its legs are steel and extend through the aluminum frame where they're flared on the inside. Too much force can let these legs wallow out the holes they're in and the tube no longer is stationary. Depending upon how loose it becomes, it can allow differing amounts of pressure to be applied to the slide stop and/or the thumb safety. The main cause I've seen for this malady is apply too much force to the slide stop plunger when reinserting the slide stop when reassembling the pistol.

The spring-loaded plungers tensioning both the slide stop and the thumb safety can be seen protruding from the plunger tube, which is staked to the aluminum frame. If the front plunger extends outward too much to somewhat easily allow the slide stop to seat that you retract it a bit. Don't just force the slide stop into place. That is guaranteed to eventually loosen the plunger tube and has the potential for severely degrading reliability.

Conclusion & Observations: I like lightweight 1911 type handguns. I lean toward the 5" gun but have no arguments against the 4 to 4 1/4" Commander size versions. They allow for very comfortable concealed carry of a relatively potent full size defensive arm. They can stand considerable shooting but will not handle the extreme amounts that the steel frame guns can in all likelihood.

Were I only going to own one 1911, it would not be a lightweight. I am a shooter and folks reading this probably are too. Were I going to own a couple of 1911 forty-five's, one very well might be a lightweight.

I see these as filling a specific niche for the handgunner as either an exceptionally easy gun to carry concealed or even as a backup that is the same as his primary except for its weight.

This SA Lightweight 5" is a favorite .45 ACP 1911, but it would not be my choice were I going to own but one 1911.

They do bring special concerns for maintenance but it is not difficult to meet these specific needs. I believe that they are great guns for specific purposes.

Best.